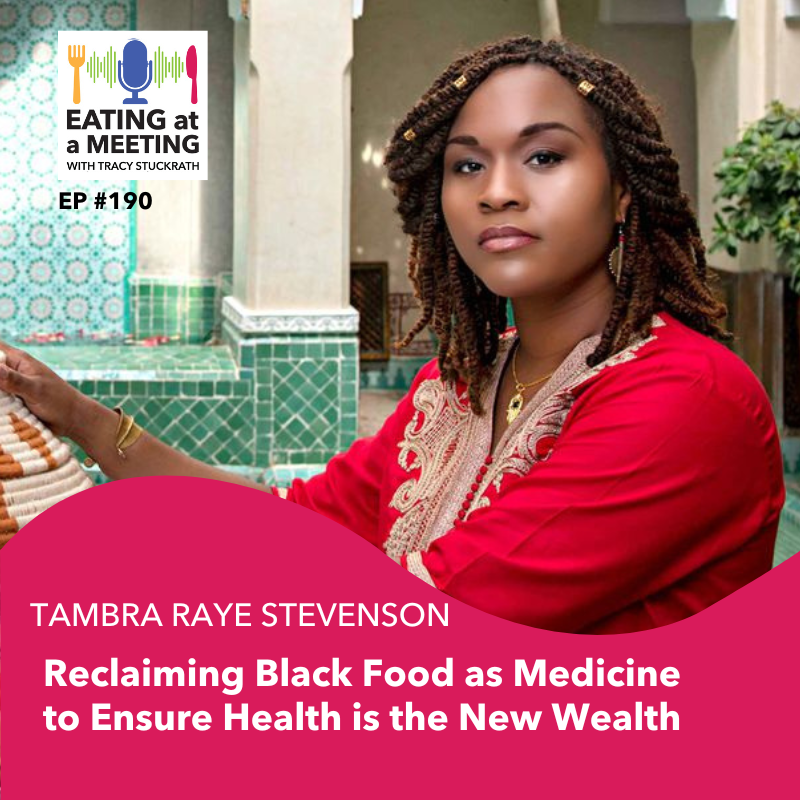

190: Reclaiming Black Food as Medicine to Ensure Health is the New Wealth

Wanting to honor the ancestry within her, Tambra Raye Stevenson, MPH, Founder/CEO of WANDA (Women Advancing Nutrition Dietetics and Agriculture), is addressing the challenges of our current food system with Sheros and advocating for a Food Bill of Rights.

Tambra lost her grandparents in Oklahoma from diabetes, stroke, and heart disease due to diet and our food culture predicated by the policies set in our cities, states, and country. So she takes the issue of public health and food and nutrition policy personally.

As a mom, she began thinking about what are we telling the next generation about food, nutrition, and the culture of food. Through WANDA and Sisterhood Suppers, she is bringing awareness to how food is connected to our health, economy, and environment.

Join Tambra and Tracy on Eating at a Meeting LIVE for a Women’s HERstory Month episode to discuss how she is revolutionizing our health and culture of food through the power of women and girls, amplifying the importance of a Food Bill of Rights, and why a Black Food Census is needed now as we prep for the Farm Bill.

Heard on the Episode

"Food is powerful. It literally can help build economies. People can go to war over a lack of food." ~Tambra Stevenson (12:00)

"And that's really the key part here is being able to have something bottom up from the people to be able to say that we recognize that for too long, the system around food has not been controlled by the people itself, but by those who are profit making." ~Tambra Stevenson (24:06)

"When you have women who have walked that intersectional path of life, they're able to show and bring their full identities to the table." ~Tambra Stevenson (48:27)

Key Topics Discussed

-

Reclaiming Black Food

-

Using food as a form of medicine for wellness.

-

Highlighting cultural and economic importance.

-

-

Empowering Women

-

Role of women in the food system.

-

Initiatives like Sisterhood Suppers promoting leadership.

-

-

The Food Bill of Rights

-

Advocacy for equitable food policies.

-

Encouraging community engagement and representation.

-

-

Education & Media

-

Raising awareness about food's historical context.

-

Combating misinformation through credible education.

-

Key Takeaways

-

Food as a Cultural Pillar: Emphasizing black food's vital role in nourishing communities and economies.

-

Women's Role: Uplifting the essential contributions of women in nutrition and agriculture to reshape food systems.

-

Policy Advocacy: Promoting the Food Bill of Rights to ensure fair distribution of food resources and representation.

-

Community Engagement: Advancing education and dialogue through initiatives like Sisterhood Suppers to connect and empower communities.

Tips

-

Cultivate Awareness: Promote the diverse nutritional benefits of traditional black foods.

-

Foster Community: Use gatherings like Sisterhood Suppers to engage and educate.

-

Advocate for Change: Support food policy initiatives for equitable access and representation.

-

Educate Authentically: Share cultural stories to preserve and celebrate food heritage.

Timestamped Overview

00:00 "Silo-Smashing Nutrition Advocacy"

03:57 Exploring Black Cuisine's Health Impact

08:28 Seed Saving and Food History

12:33 Food as Diplomacy and Identity

14:59 Empowering Food Citizenship

18:56 Advocating for a Food Bill of Rights

22:57 Democracy and Food System Reform

25:25 Empowering Food Policy Councils

27:32 Sisterhood Supper: A Culinary Revolution

34:18 Culinary Reparations and Recognition

38:56 Advocating for Healthier Classroom Food

40:09 "Inspiring Food Sheroes"

46:40 Shirley Chisholm: Unbossed Pioneer

48:20 Diverse Representation Drives Success

51:43 "Wanda Nonprofit Recognized for Impact"

Like what you heard? Subscribe to our newsletter for more episodes and insider content delivered right to your inbox!

Tracy Stuckrath [00:00:00]:

Of eating and Eric heard. Go live. Let's do this again. Alright. We're good. We're live on Facebook. We're apparently not live on LinkedIn, so I'm just gonna let it go for right now. And hello, and welcome to another episode of catering at a meeting.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:00:16]:

I am your host, Tracy Stuckrath. And I this is March, and so it's women's history month. And I am so proud to be bringing to you fantastic women throughout this the month, including this one right here, Tambra Raye Stevenson. She is the, with Iamwanda.org, and I'm gonna let you explain all of that. I found her in a Facebook group and then found out she was a member of La Domce Escoffier, which I'm a member of as well. So I'm so honored to, have her here with me. So hi, Tambra. How are you?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:00:49]:

Hi, Tracy. Thanks for the invitation to join the conversation today. Yes. I'm the founder and CEO of Wanda, which is Women Advancing Nutrition, Dietetics, and Agriculture. Began more than five years ago with the focus of really creating an inclusive food system by investing in the human potential of black women and girls to unlock their inner food shero to help heal our communities one, fork at a time.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:01:17]:

I well, and I started mine. And was like, well, that's one event at a time. I wanna make things more nutritious and inclusive. So in Wanda, there's a lot in there. There's dietetics and nutrition and agriculture. So can you share with us what that means in making sure that, that we are healthier, we're more you know, we've got more nutrients in our bodies.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:01:41]:

Yeah. Being, born and raised in Oklahoma and Texas, and and going off into, nutrition at Oklahoma State, I was surprised to see that nutrition was not housed in the College of Agriculture. So these experiences over time of just being dedicated to health, through food and nutrition, understanding that our food comes from the Earth and why we should take care of that earth is the only one we have. I take a very silo smashed approach catering learned that how we were thinking about it within the federal government at HHS about bringing, you know, people's superpowers together. And so it's been that focus that has shaped around not only silo smashing sectors, but also generations and geographies and how no matter where you are around the world, how it's important for women to activate their inner food hero, because, ultimately, we are in a time of technology where we can easily, as we are on this platform, share knowledge, share best practices, and make a better, quicker impact, that we can have lessons learned from, you know, our fellow sisters in Nigeria or Ghana or anywhere else to Louisiana to California. So that's the beauty about, focusing on leveraging digital technology to help creep it, the sisterhood that can be anywhere. And that's been, one leapfrog opportunity we've taken advantage of with Wanda.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:03:19]:

That's fantastic. And the topic of this presentation, which I put in the the thing here is reclaiming black food as medicine to ensure health is the new wealth. And and I I absolutely love that because in your article, and I'm gonna share your article food, that I read, which you shared with me, was on eating food Meetings Well magazine. And there's talk about that black food as medicine. You know, I love collard greens. I never ate them until I lived in Atlanta, and they're so good. So talk to Sarah about that.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:03:57]:

Yes. It was a joy to be able to just take on this project with meetings well, working with chefs and dietary, and and just the the dynamic team, editorial team with the magazine, to do this piece. And when it came to shaping the focus of the article and even, you know, the diction and the narrative, it was very clear, that, one, we've looked at and and held up soul food and critically analyzed it, sometimes not always meetings the value of what it represented, but understood that black food, is is almost a genre of a larger collective that encompasses soul food and African food and Caribbean, and all these different ways in which we express our culture and identity. And so to be able to do really a first ever kind piece to put the angle, from a health perspective, that we know from the field of nutrition and just so timely and relevant right now and the big larger conversation of food disease medicine as a movement. And so because of the limited research investments that have been made in analyzing, the nutritional value of these black foods. It was also an opportunity to call that and invite people in and institutions to say, where are these foods on our agenda if we're truly dedicated to addressing health inequities in the black community and understanding that food has no borders. Right? There are other folks who are engaging in in and enjoying, enjoying black food culture, if you go to any restaurant, you know, here in DC or beyond. And so it gives us that opportunity to say when we make those investment dollars to understand that the data equals dollars, conversation, this is how you build local food economies.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:06:00]:

This is how you employ and create jobs, for women in our communities, because their food is not, you know, angled only in the art of, you know, you know, gastronomy, but also in medicine and being able to see the value of what it means, to equip those who are nutritionists, with that knowledge, so they can ensure that they have compliant patients who are eating their collard greens or their jamajama or swiss char or, you know, spinach, whatever kind of green that you partake in. We we we know we have evidence based practices and we need to have more evidence when it comes to the health benefits of black food. And that takes investment from industry as well as governments and for the people, to show through the power of public will that the need is there. And this article squarely puts that conversation in front of us and help to build that agenda.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:07:06]:

And and I and as I told you before we got on here, there is so much data there and so much great content in here with links to studies and links to research that show that it is that. And talking about it. When I got And it's a little bit of a tangent. I got diagnosed with food allergies, and I went to and I said, this is what I'm allergic to. And she's like, here, go eat, and this is here's follow the food pyramid. Right? And same kind of thing. It's like we need to educate the people who are trying to educate us on food, you know, about these other ways to eat, ways that have been taught. Right? Or and and I don't wanna and I said, you know, I love collards.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:07:51]:

I don't wanna put that as the the main thing. There are so many different greens out there, but we we see iceberg lettuce, right, or romaine. And, and I avoid iceberg lettuce because it's just water. Right? So I think what you're doing is so valuable. And, the and it and it's it's just showing it's not more it's not just a collard. It's got so much more to it, and that's what food is. It's so much more and I think one of the articles that you said, it's financial. It's it's economic.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:08:25]:

It's all these other things. Right?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:08:28]:

Most definitely. And, you know, to touch on, you know, just the story of Collard, I mean, in terms of it food for purposes of one of my interviews with, Bonita Adeeb who, is a part of Ujama, which is a cooperative, and in Agapeet, Maryland where they're, you know, invested in this idea and, one, building almost this underground railroad of of of seed saving and and bringing farmers on board of collecting these various varieties, from okra to millet to sorghum. And it's just amazing to know that through the work, of the kosher project, that their work heirloom collar project, that they're helping to also tell the story of, you know, how some of these foods even became demonized. And and understanding that history is something that gets lost in academia and in nutrition that takes this very biomedical model. You know, until I dived into the world of food history, which to me should just be and it should be a events course that anyone should take that know the history of the food, know the history of nutrition, to know where we're going. But she tells a story about, that doesn't get captured in this article, but just understanding how when we were building economies on collards, on watermelon, at a time in the Jim Crow era. These foods were under attack because it was a way to displace economic opportunities for black farmers. And that was one piece of historical nugget that I did not even know, but made complete sense from the black face and the of a community around dissociating yourself with your own cultural foods.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:10:34]:

And it's it's then shows how food is a form of soft power, that it you don't necessarily have to take a military might to harm a community, but you can actually use the power of food, use the power of media, and join those pieces together. To me, that was and, why events now I'm working on my PhD in media because I began to clearly understand that in this digital media landscape, people are bypassing gatekeepers, going online, getting information directly, but is it credible? Is it, truly going to help heal you, or is it going to kill you because of the meetings disinformation of of health and nutrition, information out there. So her story to me was powerful of and, this idea of being able to tell our stories and having platforms to do that and to pour that into the next generation, of farmers and nutritionists and just the beverage public to know, where we have come from and how are we going to make the future different.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:11:40]:

Yeah. And and I there was a guest that I had on the show, I think it was last year, and she's kind of doing what you're doing, but with South America. And and because we're losing the history behind our food when we're looking at media and kids are not paying attention to what grandma's cooking in the kitchen or mom's cooking in the kitchen. So those stories that were passed down from generation to generation three, four, five, six generations ago, and of like that string in the telephone, you know, you know, you're losing that. So what you're doing, I think, is so valuable to bring that back and share those stories because because it is it is powerful. When you were talking there and I know that you went to you grad you went to American University. Right? So I'm assuming that you took Joanna Mendelson's class on food diplomacy or food diplomacy?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:12:33]:

Joanna is a fellow dom, but I'm in the school of communication. She's in the school of international services, which I do have a relationship with because of the NSF Wasted Food Research Network that I'm a part of. But we, definitely, communicate to one another, but I've not had the opportunity. But, you know, her work around Kosher diplomacy and now what state department has relaunched the culinary core, is, you know, part of that soft power of understanding what food represents and how you can create goodwill, by understanding how food is an expression of identity. It's an expression of power, but it's also and, an expression of communication and and creating communion, and community at the heart of it. So I definitely see, you know, even the research, put into this project with eating well-being so important and along with, you know, empowering that knowledge, through the women of And of recognizing that we have to rethink that it's not just food for food's sake. Food is powerful. It literally can help build economies.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:13:55]:

People can go to war over a lack of food. Mhmm. And so and we can create peace with it as well. So I think food me, it was been so important to be able to just depart and reinforce something that we can easily take for granted. But we see right now what's happening in Ukraine. I mean, it literally can go to a World War three, if we know the history of how the other couple of wars began in that region. And a global food crisis is is one of those and of, you know, sparks that can really be set off if it's not controlled well and tamed. And so that's what investment looks like.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:14:37]:

It's containing a fire, and we need to also contain that right here at home, as part of our own national security.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:14:45]:

So what has your what has your been your biggest challenge with what you're doing in in getting this message across and and pushing this message forward?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:14:59]:

Honestly, I take, as I tell it to my kids, I take personal responsibility. I'm only one woman. And so if I can clone myself and make more Wanda women and and almost like a like a military force, you know, food food freedom fighters on the front line, protecting our food borders and understanding the role that we can all play as food citizens, and a food democracy that everyone has to participate and have a seat at the table. Everyone has to see that through the purchases that you make at the store is an expression of our values. It's an expression of how we care for ourselves and how can we get, an understanding of that and and direct that into participating in our local food policy councils as well as participating and setting up town halls and forums to have politicians and ask the question, where do you stand on building our local food economies? And how do we do that in a way that's sustainable? It's, beneficial to the planet. It's beneficial to the people and it helps to create livelihoods without putting, you know, this triple bottom line in, in harm's way. And, and so when we begin to think that we start to see all these other social determinants of our food system that we have to factor in. And so for me, food is just a prism into seeing a world, of how everything connects, the fuel transportation issues, just as much as the role that media plays and amplifying certain, foods over others, because, you know, we don't see advertisements for oranges, but we do for other, you know, highly processed food items.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:16:45]:

So it's it's this understanding for me that, and then especially having been a nutrition educator, in schools, in communities, in homeless shelters of, like, food is so many different ways in which you can educate someone about chemistry and art and math. It just it's amazing what you can do through the power of food.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:17:08]:

Well and I just was at I just spoke Saturday at the School Nutrition Association of Virginia, and it was I brought that topic up. I'm like, what does I asked the diet the school nutritionist, what does food mean to you? And they're like, it's nutrition. I'm like, but it's also your job. You know? And it's the farmer's job and it's scarcity and it's danger for some. And there's like you said, I mean, you gave great examples of that. It is I and I love that that that you said it's a prism to see the rest of the world. I really that's beautiful.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:17:40]:

Most definitely. And that's why we've been, you know, since last year before the White House conference on hunger nutrition had occurred, put in the policy recommendations to the White House around supporting the food bill of rights, because by, doing so, it it really begins to look at the right to food as a value that Americans care about and really are willing to document that since we love putting pen to paper on things that matter to us. And so the idea is to help inform the future food and nutrition allergies, policies in which we, bring, we we we craft, we implement. They tend to be and aid approaches to work, on the immediacy, the emergency issues in a time of crisis. And if you think about it through the lens of health and medicine, you have an ER. Right? And we always talk about in public health, if you wanna save money, you try to reduce people from going through the ER for an issue that does not deem at an emergency level. Go to urgent care or go to your local community clinic. You save health care dollars.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:18:56]:

Well, this is the same approach public health approach I see to food. There are moments when you have to address emergency hunger issues and you need legislation enacted immediately, but then there are other times where it takes a more preventative approach because you've already put a long term plan in place. And that begins to thinking about, well, what is the value system? What are the vision that you're setting? And so I think we have not done that as a whole, as a country to say, these are values and how does that, you know, flow to the state level, the local level, through our food policy councils to say, we have not just an emergency plan, but we have just a general plan around building our economy around food and in a way that is helpful as whole, and it and it allows the sense of food sovereignty, the dignity and respect that, food deserves and the people who consume it and those who work in it. And we have not gotten there, but the Food Bill of Rights gives us this opportunity to put pen to paper. People can go to iamwanda.org/foodbillofrights to sign the petition. We see that the upcoming farm bill, happening right now over the next eighteen months, as it goes through its transformational process that we call upon congress to think about incorporating and enacting a a food bill of rights within it. That would be one way of looking at how, nutrition is a big component of that farm bill and how can that be parley with this framework, a unifying framework to think about, and to do something about how we value food in this country. We've, we have it in the UN declaration of human rights, the right to food, but nothing in a detail that industry, as well as government can buy into.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:21:00]:

And and if nothing else, organizations can begin to incorporate, this concept and look at operationalizing it when when it comes to meetings local models. We've already had it as a priority adopted by the DC Food Policy Council to to research and to investigate how, it will be situated at the local level. But, ultimately, it should be one adopted at the national religious as we most recently adopted the AI bill of rights, that happened immediately right after White House conference back in halal of twenty twenty two. So this is something that, if we can have a AI Bill of Rights, we can build the momentum, to have a food bill of rights as

Tracy Stuckrath [00:21:49]:

well. Yeah. Oh, I agree. And it's it it's going to the being at that conference the other day, it it's it I saw the cumbersome, and I know the cumbersomeness of the food when we're thinking about it in an event meetings. But even just trying to feed our kids. Right? Going down the aisle of these food manufacturers, you know, repping their food to get into the school system, they're showing that it needs one, you know, thing of of fruit, and it needs one thing of beef or, you know, meat protein thing. And but it was interesting. I'm like, okay.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:22:27]:

They're like, do you wanna test it? And I'm like, well, only if you can tell me what's in it because I've got food allergies. And it was amazing how the first fifteen people could not answer that question. And I'm like, so it's it's very capitalistic, the food system is. And there's a lot of things that get lost in that. And not that we shouldn't be earning money from growing food, but I think we need your bill of rights is is changing the perspective of how that is looked at.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:22:55]:

Right.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:22:55]:

And managed. Right?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:22:57]:

Yeah. It's it's similar to, president Biden at the time calling, for us to double down on on democracy in America and in being a role model of that, especially after the the insurrection of January sixth. And so food me, this is this flows right into every sector of how does democracy show up. It's not just democracy showing up at the voting, booth, but also when it shows up to, voting for what kind of food system that you want. And, what happens as to the analogy of of the ER is that if you have too much and this is why capitalism can get a bad rep is because when you do too much of anything, even if it is food, I can have too much water, hydrotoxicity, and that can be a bad thing. And so you have to think in the same way of of the food system. If we have food, much power in a few hands and that power is not distributed across the board, how can you truly say you have a democracy of everyone participating? And that's really the key part here is being able to have something bottom up from the people to be able to say that we recognize that for too long, the system around food has not been controlled by the people itself, but by those who are profit making. And no harm to that.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:24:27]:

However, that does not mean that we should also not have a seat at the table. It's almost like saying in congress of the house of representatives that we're only gonna give the North votes, and the South, you get no vote. But you can come and join and watch us. We would never sign on to that. This is what civil war would lead to. So why and and then this is why senator Booker and so many others have called on this nutrition food crisis that we have is because we do not have and equal balance of power of how people are able to express what what kind of food, democracy, should look like and how can they participate. And right now, if you look at a recent report from events for lovable future at Johns Hopkins, on local food policy councils, some are housed within government, some are nonprofit. Every state does not have them.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:25:25]:

Every city does not have them. And these are mechanisms in how people can express their democratic participation in the food system. So if I'm in Oklahoma City or in Dallas, Texas is where we have had sisterhood suppers bringing women together to talk about what does food look like in your city, how are you able to articulate and organize and mobilize to change that, there is a lack of, no and that that that is a problem. And so the idea is we need individuals to feel empowered that they have mechanisms to be able to channel their voice. And right now, those mechanisms are not in place and equally distributed across our states, across our cities. And for those who do have food policy councils, that is a mechanism to do that. And so that that's why we have such a great opportunity now coming out of post White House conference of what will the next few years look like and putting these, the this infrastructure in place for people to participate.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:26:33]:

That's and and I'm I started the other day when I was looking reading your article to look up the food policy for my area in in New Bern, North Carolina. So I'm I'm I'm gonna say we're rural. We're a town of 30,000. Right? We're not Washington DC, and I lived in Atlanta for twenty two years. And the food is much different here and the access to food and and not to my the the farmer's market here, I think there's four farmers out of 50 vendors in our farmers market. And I'm like, come on. Let's let's where are our farmers in this area? Right? And making sure, like you said, it's not in every you know, it's not the same in DC as it is in New Bern. So how do we grow that? So you've just and, you know, lit a fire under my rear end to do something different and and see what we can do in this community.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:27:25]:

Right.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:27:26]:

Yeah. So I love the fact and I was gonna ask you about sister's supper. So talk about what that is.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:27:32]:

Well, sisterhood supper, began well before and by 2017 in homes meetings, having those dinner conversations that really was, an opportunity to be the anti Sunday brunch. The anti Sunday brunch in DC, it's almost a religion here, where people go to restaurants, they come together, they gossip maybe around superficial things. And so, yes, your money is going to a restaurant, but what if you actually brought it in house, in home, prepared a meal that was good for the soul, and you had conversations of substance? And so my brain thinks like a cultural engineer. How can we reengineer how we think about the ways and norms of life? And for women, we know we have moved ourselves out of the kitchen as a form of a liberatory tool, but yet the argument for me is the power is in the kitchen. Because depending on who controls, not only the food of where it grows, but who prepares it can be a matter of life and death as anyone knows who's had a food allergy. And so the opportunity for us was to expand it, especially during the midst of the pandemic. We had, launched our Wanda Academy with the support of Sibley Memorial Hospital in Johns Meetings, and we wanted to conclude with a sisterhood supper. And we thought, like, why not open it up to the community and not just to the cohort? And so it became now an annual event on Juneteenth.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:29:14]:

Now this year will be the third year where we hold a community sisterhood supper for, one acknowledging women who have been those food heroes, helping in the midst of this pandemic. But everyday women who are food heroes, whether they're have restaurants, retail, outlets, or producers, or caterers, or educators, or events. We wanna uplift those voices and show other women that we have women on the front line beverage day meetings to feed and heal our communities, who are role models for our girls. And we bring other women together. We workshop. We have the unveiling of the food bill of rights, getting their voices, creating that discourse around supper time, and and having a celebration while you're at it, and being able to pick food from the local farm that we host, our event at. And so it really is making that connection from farm to health. And so DC Greens has been a dedicated partner, in hosting, this sisterhood supper in our community.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:30:21]:

But it's been one that we've used as a way to talk about policy issues and meetings restaurants and in homes. And so it's a variety of settings. And so what happened last year, which, was a proclamation by the mayor to, to acknowledge a Wanda week. And that week is about celebrating the culinary contributions, of black women in the food system in agriculture, nutrition, and dietetics. And so we are looking to host sisterhood supper celebration kicking off Juneteenth as well as Wanda week, this year in June as well. And it was an honor to, speak to Opal Lee, who is the grandmother of Juneteenth, who was able to get the federal holiday, passed by president Biden, just in 2021 and recognized that, she too is definitely a part of this movement of food freedom. And Juneteenth is known as freedom day for many, especially down south, where my ancestors are from Texas, but still enslaved even after emancipation. But understanding that food can be an extension of this conversation of freedom and what she's doing with her farm down in Fort Worth, being able to grow food and share and heal her community.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:31:48]:

She really embodies the essence of a food hero. And so we're looking to share her story, and as well as so many others in our in our upcoming and forthcoming book project as well as for Juneteenth. Because when we don't amplify the women who have been a part of the everyday of improving our lives, these they are just hidden figures in the food system, and we say no more.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:32:15]:

I I I wanna be I don't think I can be there, but I wanna come. I that's phenomenal because it is and there's a lot in there to unpack as well. I mean, the fact that you you did say we've taken ourselves out of the kitchen because we didn't wanna be there, but it is that's you know, conversations with your grandmother happened around the kitchen table while you're snapping beans or, you know, things like that and but also the value and the importance of the nutrition that we're eating. So and and I I do like the fact that you said the hidden figures of food. And there are so many different people in the food system that are hidden Mhmm. That we don't recognize. We only see those chefs on TV, and and that's not reality.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:33:03]:

Most definitely. I mean, so many women like Leonard, like, Lena Richard, who was a well known New Orleans Caterer. She was a food personality and really made a name for herself, created a cookbook as well. But who knew about her? I didn't know her, or women like her. And my nutrition classes, we didn't even talk about the people except those who were the researchers. And I think that's a real disservice when we don't acknowledge that before the field of nutrition even came about, who were the first nutritionists in our lives. And it tend to be that grandmother, that auntie, that mother, and to not, and when you would grace the role that women have played and and now the the the title of chef has been elevated where we see mostly men leading in that space, which that too is part of gender equity. But it should not be by stepping on the backs of women to do that without giving them their proper due and acknowledging the culinary currency that flowed in their vegan events when they were not paid events tenth of what they were owed.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:34:18]:

And so there is a sense of culinary reparations around this work. Of acknowledging that as we move forward and who gets to make what dish, what is what is the credit, what is the coins, what is the credentials, that come with it, because there was erasure of even women like, Rashard around whose recipes, were given to whom credit was neither disease, but it was just the way power structures were. And so you can call them, you know, black women being seen as a ghostwriter for white women at the time in the South, but it was something that, is is a is a falsehood to to acknowledge and and to repent. I think that's the inner Catholic in me, and to say what will be the events owed, for these women? And those who have made a way to heal our communities. Like my ancestor Henrietta, in Texas and Navarro County. So it's because of her and knowing my own family history, and so many others who I encourage you to know your history and use these kitchen conversations in your own home, whether it's a family reunion. But it's that assignment, of having to do a living history interview, while I was an undergrad at Oklahoma State that made me see, wow, the power of, of interview of just sitting by someone's, you know, side and just hearing their story, how that story is not only medicine for them, but it's medicine for my soul. And I I'm forever changed because of valuing the lived experiences events so many times we're told that we should value some other person's experience that has no direct effect on our lives.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:36:19]:

But it's the people who we're surrounded by have more of an impact on our lives and more of a reason why that is a form of wealth and their knowledge and how we can pass on that knowledge to our generations. Otherwise, we'll tell ourselves stories, when we need to be writing new chapters in our heads.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:36:38]:

Right. Right. And using AI to do that. Okay. So in just writing our future, you've got two kids. What what do you see for them? What have they learned from you for the future of that their nutrition? And and what do you say for other women, you know, that are there because they're 12 and 13. Is that what you said? Yeah. You know, for kids their age going forward in this and understanding where they're headed with nutrition?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:37:13]:

Well, food mine, early on, I exposed them to, not only food toys, but also nutrition education, taking them to the local community farm, but recognizing that the food that you're eating has a plays a critical role to your health because not even I knew that growing up as I ate the honey buns and the sodas, not even knowing there was even a career in nutrition. And so now, you know, I could see my son this week just eating a carrot like Bugs Bunny, right, while he's watching YouTube channels around, nutrition that I didn't even prompt or watching conversations around just medical stories and and really being engrossed in it. Even though he has a whole career focus around robotic engineering, you know, maybe one day he might change to biomedical engineering, not realizing how early on those seeds were implanted in him to see the importance of nutrition and health and how they are not only good for your body, but you can build a career out of as well.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:38:28]:

That's awesome. Yeah. Because there is there's so many things that you can do, and we take it for granted. You know? And and I was actually in the food exhibition at the Smithsonian, on Friday, and they had the machine that made the first Krispy Kreme donut. And I'm thinking, who came up with this idea, you know, to do that? Really loves donuts. Apparently. But your son could be the next Krispy Kreme donut, you know, maker machine maker. Right? Right.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:38:56]:

And I and and that's what I tell them. You can either use your force for good or for not. And Mhmm. What do we need more of? Do we really need more donuts to feed the world, versus more plants? And so, he was never the the avatar in my mind. When I created Wanda, it was clear that my daughter, who she would probably now have issues with me talking about it, but she had, you know, cavities early on, and seeing the role that her teacher providing junk food as rewards to her and her classmates as a way to manage behavior in a preschool classroom was vegan catering to me. And even though I showed up to the PTA where they talk about you should be involved as a parent, well, my words fell on deaf ears. So what was the point of being involved? And so that's when I started to see the connection. Like, how can I be advocating for food policies in the city when I can't even make an effective change in the classroom for my own daughter? And that disconnect really bothered me.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:40:09]:

And it said to me, one, pride ask probe and ask questions such as, you know, what are you feeding your own children? Would you allow the same in their classroom? She's saying no. So why is it acceptable here in Anacostia compared to your neck of the woods? And realizing I could either be mad or I can do something about it. And that's when I started writing a children's book so I can go into classrooms to help tell a new narrative, and using little Wanda as that aspirational character, to inspire elementary kids to see themselves as a food shero and really thinking how can I, in essence, turn this teacher into a potential food shero, and get her on the winning side that she plays an important role, not just through education, but nutrition education as well? And so that's where the first seeds of thinking about Wanda came to mind, is growing up in a military town of Midwest City, meetings Air Force Base, and thinking how can I, you know, turn the average day citizen into a a a fighter for for food, for freedom on the front line? And that's been my mission ever since.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:41:33]:

Well, I just found it online, and I posted it in the chat of your book, on on Goodreads. And and and that's what we need to do. I mean, talking to a local farmer here in Vegan Bern, you know, he I'm like, oh, go talk to the caterer. And and he's like, well, the caterer said to me, I don't only if you can give me the prices that I can get from the big distributor will I buy from you. Right? And he's like, I don't wanna use that. And it is strictly on his bottom line, which is his his prerogative. Right? But it's like getting helping Steven, you know, get that get his food into those other avenues of it. And and, I mean, his food is in my kitchen, but I wanna get his food, you know, further out, you know, to the bigger meetings.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:42:18]:

And that is the work that you're doing and becoming those advocates and and and food fighters and sheroes. And I love that word. So thank you for introducing that to me. And of the other things that I noticed, and we're coming up on forty two minutes. Woo. You met you mentioned you have asked readers to take the black food census. Can you speak to that?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:42:41]:

Yeah. It's really the first ever since it's focusing on black food, as a culture and how it shows up in media in particular, whether it's the publishing, digital space, apps, but really understanding, when we don't have this awareness, we have this omission. I've seen a a sea change, slowly happen with some apps. Before, you would not celiac category for African food or for soul food if you're looking to order food and delivery apps, for instance. And that sense of erasure was problematic. Some have gotten better than others, but it's really taken a stock of what people are seeing in their everyday lives when it comes to, making decisions about what services are in their community, what is not, and what information, devices they have and what do they see, on those devices. And the idea behind it is, again, if we don't have the data, we can't make any strong arguments food making any changes, whether it's to industry, in the tech sector, or if it's to government, about understanding the role that media and technology play in food. And we're not having those conversations as we're seeing in the digital health space.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:44:06]:

But at some point, that needs to be that conversation in the digital food space as well. As, you know, countries like Austria, Australia, The UK, they have been building the academic canon in this space around digital food studies. And I think, we have an opportunity to make a contribution, as it relates to a subgenre around digital black food as well.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:44:35]:

Okay. I that I I love that because when you're looking at it but it's in then also educating us on all the different cultures of food, and and black food is one of those things that and I think it's associated with southern, you know, and and then it's bad, and it's macaroni and cheese, but it's in in your eating well article, I you everybody needs to read it because it's really good and explains all of that about it. How who You've mentioned some ladies that you really admire. What sheroes do you have that have and what advice have you given been given by them in the work that you do?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:45:16]:

Well, that's easy, doctor Creighton's. Like, get your doctorate. Well, anything that I start, the idea is to finish. My mom said that as well. So it took great trepidation even when I decided to start because I knew what the voice was in the back of my head that if I begin this race, I must finish the marathon. And so that is one parting piece of wisdom that I would share to others as well. Be careful what you start because you must finish. Partly, that speaks to just that have a rough first draft.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:45:55]:

I'm still working on the adjective. Right now, you're Partly because it speaks to this idea of if you don't finish, there will be that part of you that will say, what was the regret? And we don't wanna have any regrets in the back of our minds is the critical part here.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:46:15]:

Thank you for that message to me personally as well because I take that to heart. I somebody said that to me the other day. What I started, he's like, you're still tenacious about it. And I'm like, I am. And so know that. Shirley Chisholm, tell people about who Shirley Chisholm is and how she empowers you.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:46:40]:

Yeah. Shirley Chisholm, origins of The Caribbean, 1 of the first black women to run for the seat for president here in The US, was one of those women who said it best that if you don't have a seat at the table, bring a voting chair. And so she was definitely unbossed, unbought kind of spirit, who also advocated, very much for some of the programs that we have today, WIC and SNAP. And so she definitely was a voice of of black women at a time in politics that was not very common but necessary, which is why I know she would sign a food bill of rights because she understands the importance of power to the people and being able to see your power and use your power in a way that truly helps all and not some.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:47:43]:

I was trying to put you on the screen by yourself, and I put me. Sorry about that. And it is. And I And and I love that table. Bring your own folding chair. That's that's fantastic because you do. You do have to do that. So what as a because Wanda is all about the women, in nutrition and dietetics and agriculture, what is what's the important for you as a woman? You've kind of said it, but going forward, the importance of women in the food and beverage industry.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:48:20]:

Well, as I shared earlier, anytime you have one group of of, let's just say, call it, you know, hegemonic power, you have to acknowledge that that comes with a very narrow lens and does not provide a wider lens to view any blind spots that others and their own lived experience brings to the table. And so when you have women who have walked that intersectional path of life, they're able to show and bring their full identities and how, it can not only be good for business. We know that from the research done about the power of diverse boards and corporations that it it's good for the bottom line. They're able to expand and open up markets because of the representation, that they exhibit. And also they're able to bring if they're allowed and events permission to bring their full selves, they're able to do it in a way that speaks to a value of authenticity that we are so malnourished, in our industry, in our country of looking for a sense of truth and a sense of justice. And that is why it's so important to have full representation at a time like now.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:49:45]:

Yeah. I love that. Okay. So one two final questions. One is what is your favorite food and drink?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:49:59]:

Well, Zobo, which is a Nigerian well, specifically, how's the name for hibiscus? Just had it this week and I make it from the hibiscus flower. And favorite food, so many to choose food. But this week, I just had okra and tomatoes that I really enjoyed making. Love them. Yeah.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:50:29]:

Do you stew them?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:50:31]:

It's I mean, it's stewed in my at iron skillet.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:50:37]:

Okay. Gotcha.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:50:38]:

Yeah. But Yeah. It's it's something that, part of a series for US Botanic Garden that me and my daughter made, and now she's hooked on Oprah and enjoys it. So to me, that's a win for someone who loves meats and sweets. And so anytime I'm able to get a win on green veggies, it's always a golden moment.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:51:02]:

That's fantastic. Okay. So and my last question for women's history month is how do you wanna be remembered in history?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:51:13]:

The by the way in which I live, which is living a life on my own terms and with no regrets.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:51:22]:

That's fantastic. Awesome. Tambra, thank you. I I should pronounce that beverage. Tambra, so everybody's hears the b in there. How can everybody get ahold of you? Where you mentioned the bill of rights. I put that link into the chats on everything, but there's your website. Any how else can they connect with you?

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:51:43]:

Yep. On social media at Tambra Gray, on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Facebook, and also at I am wanda o r g. You can find us on the same channels and definitely sign up to our newsletter to stay connected. And, also, I would be remiss, to acknowledge, a recent win for Wanda was, being a part of a new, cohort with other black women nonprofits and Ward 7 And 8 through the financial support, of JPMorgan and Chase, as well as the nonprofit Foundation Center being able to provide, the capacity building to help scale up our work. And so, it's it's organizations and and the women and men behind these initiatives that are understanding the importance of investing, in women, like me and organizations like Wanda, that we need to acknowledge the role that small nonprofits play, in being these keepers of the culture and the community. And so, I hope this is a message to others that, you know, we're worthy of the investment, and and to do that at a time of women's history month is making her story shine. Thank you.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:53:03]:

You're welcome. Thank you. Alright, everybody. Thank you so much for listening, and these videos will stay in posterity on on whatever channels that you listen to, and it will be coming on audio, next month. Until next week, stay safe and eat well. And, Tambra, thank you so much for all of the work that you do now and in the future.

Tambra Raye Stevenson [00:53:24]:

Thank you so much, Tracy. Have a blessed day.

Tracy Stuckrath [00:53:26]:

You too.

Founder/CEO of WANDA (Women Advancing Nutrition Dietetics and Agriculture)

Tambra Raye Stevenson, born and raised in Oklahoma and Texas, developed a passion for nutrition while studying at Oklahoma State. Surprised that nutrition wasn't part of the College of Agriculture, she dedicated herself to understanding the critical connection between food, health, and the Earth's well-being. Her career led her to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where she embraced a collaborative, "silo-smashed" approach, advocating for the integration of various sectors, generations, and geographies. Tamara champions the empowerment of women globally to harness their "inner food hero," leveraging digital technology to connect and share knowledge across borders—from Nigeria to Louisiana, or Ghana to California. Through her efforts with WANDA, she promotes a digital sisterhood that transcends boundaries, enabling women to make impactful changes in their communities and the world.